[ Prologue, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, Epilogue ] Videos Actions

Prologue >>

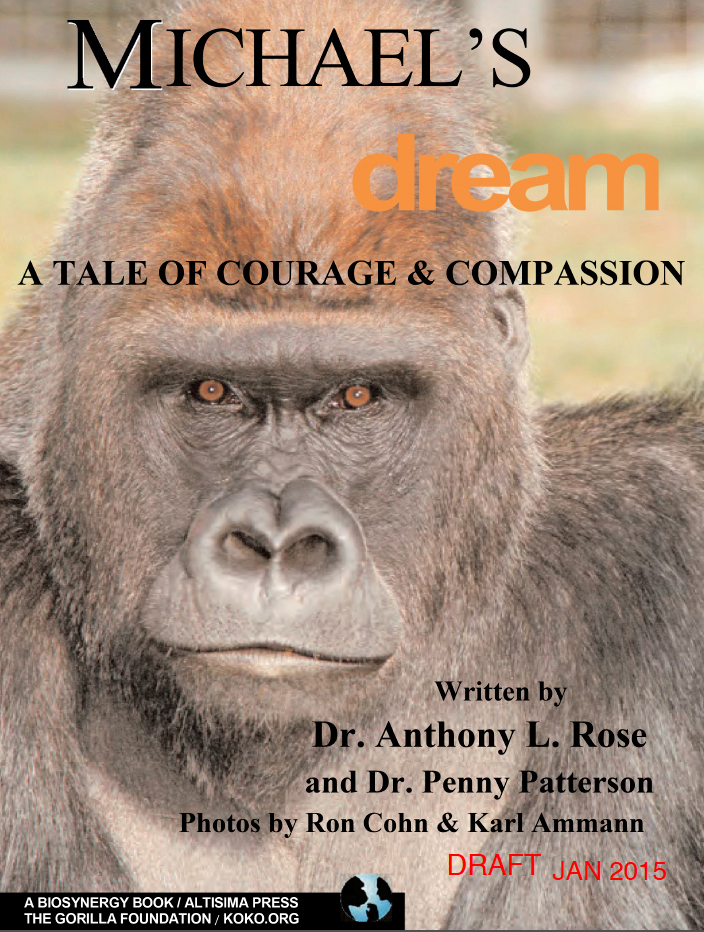

Written by Dr. Anthony L. Rose with Dr. Francine “Penny” Patterson

Copyright © 2015 The Gorilla Foundation / Koko.org

In memory of Michael [1973 – 2000], the gorilla who was born in Africa, grew up with Koko,

and became the second gorilla in the world to share a sign language with humans.

PROLOGUE

Apes and monkeys can teach a lot to people if we take time to watch, listen, and talk with them. I know from my own experience.

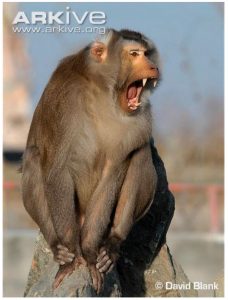

In the 1960’s I was doing laboratory research with a macaque monkey named Snicky. He was a youngster when I met him, but after two years he had grown big and strong. Each day he’d snicker and coo at me when I walked into the lab. He liked it when I cooed back, but not when I put him in the experimental chamber. Then he got upset and angry.

In the 1960’s I was doing laboratory research with a macaque monkey named Snicky. He was a youngster when I met him, but after two years he had grown big and strong. Each day he’d snicker and coo at me when I walked into the lab. He liked it when I cooed back, but not when I put him in the experimental chamber. Then he got upset and angry.

One morning I was visiting another scientist when the custodian came in and told me one of my monkeys had escaped the cage and was wrecking the laboratory. “Will you help me capture him?” I asked. The janitor said, “No sir, it’s your monkey,” and walked off. I rushed out and ran up the hall. This was the first time I’d faced a monkey outside its cage. I was scared.

I shut the door behind me, peered through the shadowy light and saw Snicky on a shelf across the room. He was pumped up, his hair on end, teeth bared. Frightened, I cooed at him — our usual morning greeting. He shuddered, jumped from the shelf, landed in my arms, and held on like a child clinging to Dad for safety. I sat down, held him, felt deep remorse, and decided to stop experimenting on monkeys.

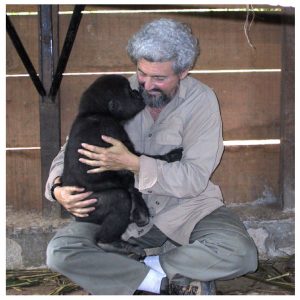

Many years later I went to Africa to work in wildlife conservation. At the Mefou Primate Sanctuary in Cameroon (now run by Ape Action Africa) I met Bobo — a gorilla orphan whose family was slaughtered by bushmeat hunters. I sat and held him, as I had Snicky, and vowed to devote myself to teaching compassion for primates. My first step was to go to the rain forest to ask hunters and villagers about their experiences with great apes.

I found that people who once revered the apes had learned from colonials that wildlife was nothing but meat for the table. Traditional respect for great apes needed to be revived, and people who slurred them had to recant and acknowledge that apes are kindred animals to humans. Only by changing minds and rebuilding African people’s compassion for the apes in the forests, would the slaughter stop.

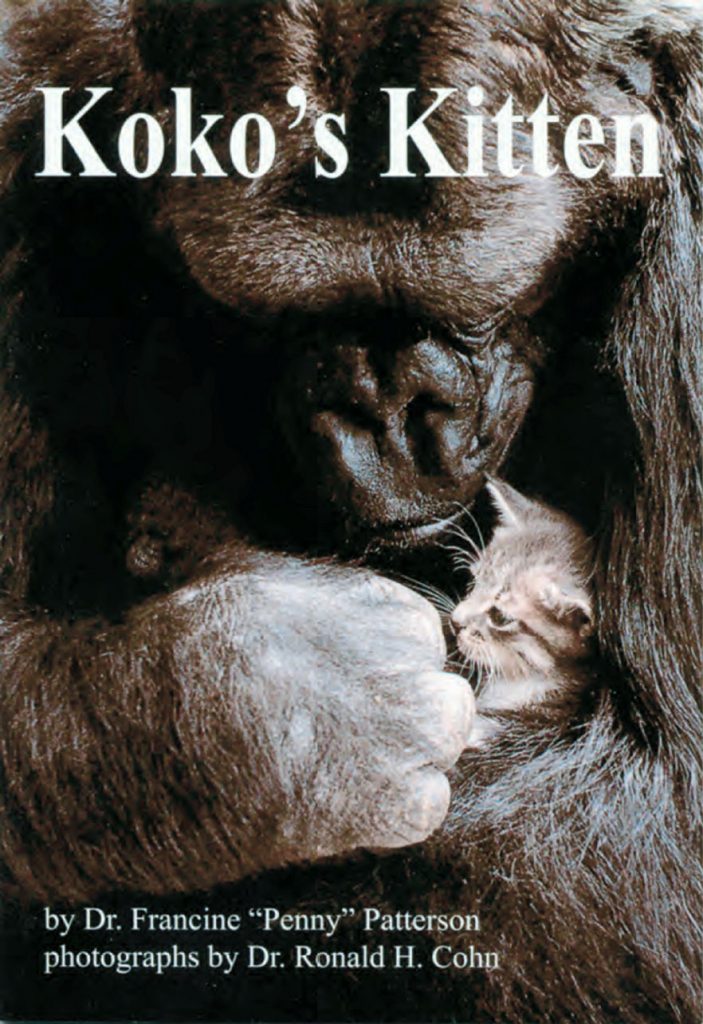

Penny Patterson (President of The Gorilla Foundation) asked me if her book, Koko’s Kitten, might change the minds of poachers and ape-meat buyers. I took the book to Cameroon and read it to Joseph Melloh, a gorilla hunter I’d helped become a gorilla protector. He was overjoyed to know that great apes could talk with people. “I have seen them talk with each other in the forest. I must tell my friends so they will stop killing gorillas and chimpanzees.” A few months later I received a letter from Joseph, reporting that he had talked about Koko with bushmeat hunters; they were moved and wished to stop poaching apes.

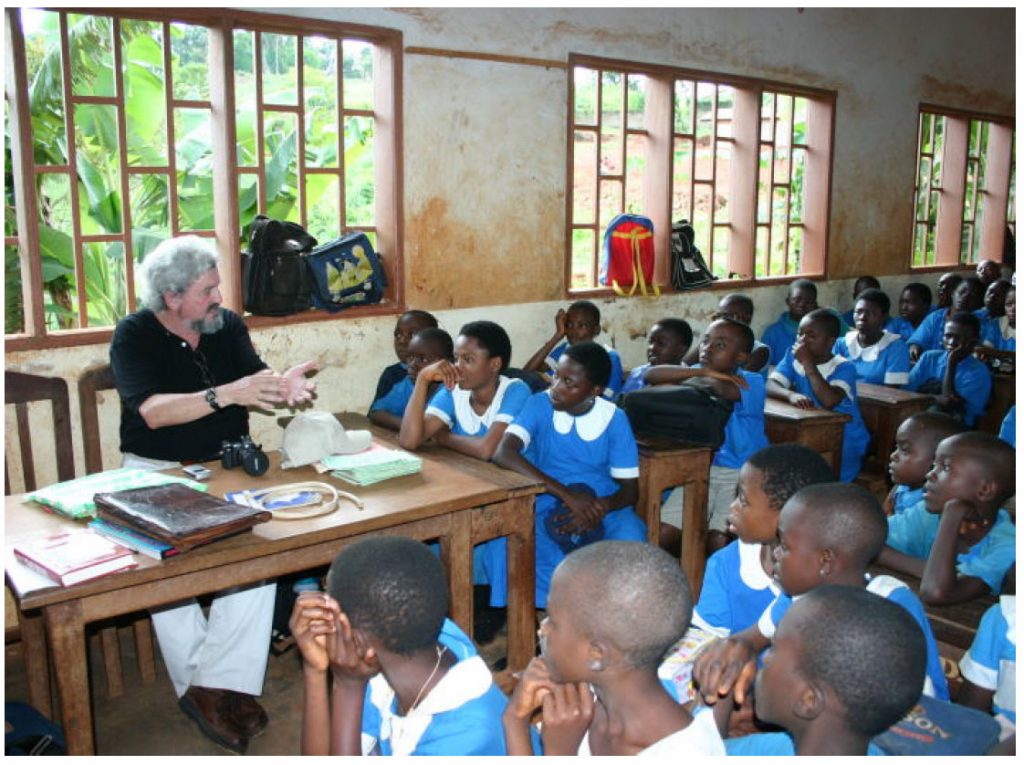

While Joseph built empathy for apes in the bush, we began teaching in towns and cities. Since 2000, The Gorilla Foundation has sent over 25,000 copies of Koko’s Kitten to Africa. The book has been read and discussed in over 500 schools, churches, and communities, causing at least 250,000 people to appreciate the emotions and intelligence of gorillas and other great apes.

While Joseph built empathy for apes in the bush, we began teaching in towns and cities. Since 2000, The Gorilla Foundation has sent over 25,000 copies of Koko’s Kitten to Africa. The book has been read and discussed in over 500 schools, churches, and communities, causing at least 250,000 people to appreciate the emotions and intelligence of gorillas and other great apes.

With the aid of our partners — the Unite Africa Association (UNAFAS) — the tale of Koko befriending a kitten and mourning its death has made teachers, students, and their families affirm: “the gorilla has feelings like people — we mustn’t eat gorilla meat!” Still, declarations of concern do not always translate into societal change. When one family stops eating ape meat, another may take up the practice naively. A bushmeat trader who refuses to sell primates will see other vendors replace her in the market. If a hunter decides to stop tracking apes, another hunter can fill his niche in the forest. We need to change social systems, to sustain compassion for primates.

Storytelling is a powerful social tradition in Africa. When a folktale is shared in a community, its message attains social credibility. If the story is repeated often, becoming legend, it has sustained influence. Koko’s story evokes lasting empathy for gorillas, in urban areas. It has less enduring effects in forest communities. some hunters see Koko as an American gorilla who is different from the apes of Africa. Village elders often recite the poignant legend of the hunter who caringly spared a mother gorilla, after she begged him not to make her baby an orphan. “If you can show us an African gorilla wih those sentiments, we can enforce the ban on ape hunting,” they’ve declared.

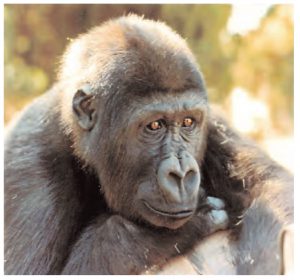

So we began to tell a modern story that would reinforce that old folktale — the story of Koko’s adopted brother, Michael. We’ve talked about Michael in many villages and in many dialects. The effects have been striking. Elders and village leaders are moved to make ape-hunting taboo again. Hunters become visibly disturbed, then silent, as if ashamed. We believe that Michael’s story, if integrated with local legends, can motivate the sustained social change required to convert hunting societies into great ape guardians.

What makes Michael different is that he was born in Africa, poached as a youngster, and then came to live in America with Koko (after being adopted from a zoo in Switzerland). At age eight Michael began having nightmares about the murder of his gorilla mother. He signed his horrible dream to Penny, and it was recorded on video. People who see and hear Michael’s brave tale feel compassion for great apes and want to protect them. We hope you will too!’

Here is Michael’s story.

Prologue by Dr. Anthony L. Rose , Palos Verdes, California USA

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Michael passed away in the year 2000, suddenly from a disease called Cardiomyopathy (an enlarged heart) which is very common in male captive gorillas, possibly because of the stress that a silverback experiences when unable to have total supervision over his family group.

The Kids4Koko Pledge

As a “Kid for Koko,” you are the key to waking people up to the importance of treating other intelligent species and our planet with love and respect, and ensuring a brighter future for all.

If you agree, please sign the Kids4Koko Pledge and share with your friends.