Article by Penny Fraser, WPF Cameroon County Director.

Collaboration with the Peace Corps started with two volunteers, Brian Gearing and Erin Swaider, a married couple, who were working as teachers in a remote town called Bafang, in the French-speaking West Province of Cameroon. Despite living in such a remote setting, they linked themselves into the informal Cameroon environmental education network and started a collaboration that now extends across the country.

When the couple arrived in Bafang, they started to look for environmental groups in

their local community, groups they could work with or assist in some constructive way.

They found themselves helping a local nongovernmental organization called The Bushmeat Crisis Discussion Group to run activities for children from the environment club in a local school. They were using Koko’s Kitten books.

Erin and Brian came to Yaoundé with these colleagues to attend a workshop that was an initiative of Chris Mitchell, the English former director and founder of the Cameroon Wildlife Aid Fund (CWAF), which manages the Mefou sanctuary, home of Michael’s Memorial Enclosure for orphan gorillas. The workshop, sponsored by Wildlife Protector’s Fund- Gorilla Foundation, brought people together from all over Cameroon. It was called “Towards a More Integrated Environmental Education in Cameroon.”

Our Conservation Values Program was just one of about thirty projects presented there. Erin and Brian were looking for projects and were keen to find ways to apply WPF ideas in their Bafang region. After spending some time discussing the Conservation Values Program, our proposition at that stage was that they take our materials and reports and experiment. We suggested they take advantage of their experience and knowledge of the schools, kids and communities that they were living and working with, and see how they could use WPF-GF resources for wildlife conservation education in their local context.

Brian and Erin taught in the same town, but at different schools. Erin was teaching science in a secondary school and Brian was teaching English language in a technical school, where students went to learn practical professions. The technical school where Brian taught was well built, but Erin worked every day in a structure that resembled, or in fact was, one large, flimsily built barn or warehouse with loose hard-board divisions to separate off an area for each class. The noise of large teacherless classes of children carried through to test the concentration of those trying to work in other “rooms.”

I travelled the five hours by road to visit Erin and Brian and to observe the teaching interventions they designed. They were both very imaginative and had spent many evenings in their small, dark, wooden house preparing lesson plans, thinking about and discussing together the best ways to focus their kids on the issues, and how to elicit and record their pupils’ attitudes and reactions to the intervention.

Erin used the Koko’s Kitten book with her biology class. She found the book useful as a tool to support her curriculum teaching and she chose to introduce it to her students when she was teaching them animal classification. As some light relief from taxonomy, she used the book to demonstrate the characteristics of gorillas, to illustrate their intelligence, their unique physical traits, and the traits that demonstrate their affiliation to close relatives. Then, the add-on that took them beyond routine curriculum topics, was to explore conservation values.

Erin asked the kids why they thought Koko wanted a pet kitten, whether they thought gorillas were dangerous, had feelings, and how they thought humans should behave towards gorillas. Erin used the pre- and post-intervention questionnaires with her students. These had been designed to assess the impact of CVP interventions on attitudes toward gorillas. She confirmed our concern that questionnaires are not the best measure of attitude.

Students are accustomed to being tested, but not opinion surveyed. They complete any

form by providing the information they believe the recipient wishes to read, and most

very quickly judged that Americans talking about wildlife wanted pro-conservation

responses. This itself indicated a certain awareness of American values. From her knowledge of her students, and how they express themselves, Erin devised ways of observing and recording their opinions–games where they had to affiliate themselves into groups, answer oral questions, and do

exercises in which individuals and groups had to write their comments privately or in front of the class.

Erin and Brian’s work in Bafang demonstrated that Peace Corps volunteers can be ideal messengers to take experiences, tales, and research from America to people in Africa. They understand the context of the American stories and are able to explain, for example, why gorillas are living in the way that Koko lives and the reasons for interspecies behavioral research, which puzzles most Cameroonian teachers. Also, through living simply in Cameroonian communities, they are able to empathize with and relate to the perspectives of their local audience.

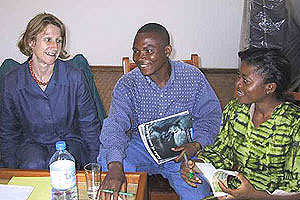

The result of our work with Erin and Brian was that WPF Executive Director Dr. Anthony Rose and I met the head of Peace Corps Cameroon, Robert Strauss, in June 2002. We also worked with George Yebit of the Environment and Agro-forestry Program and Gabriel Kwenthieu of the Education Program and head of the English Language Teaching Program, and agreed on a formal program of collaboration between our two organizations.

Meetings with the Environmental Education Committee volunteers and exchange between Penny Fraser, Anthony Rose, and Penny Patterson resulted in a Teacher’s Guide. Over the past year, the CVP has evolved from a program that was based on sharing stories from America with young people in Cameroon to one that focuses on exchange of wildlife stories, tales, and traditions.